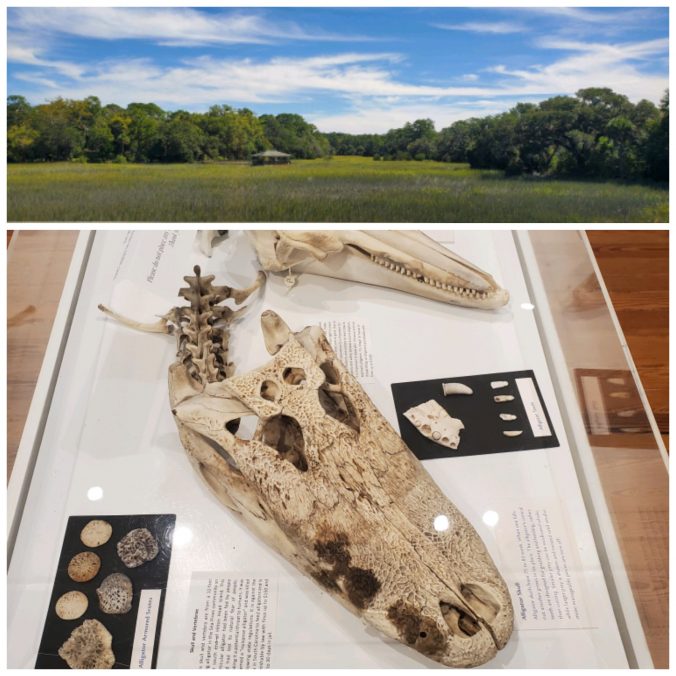

The trees of Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, tell a story.

As a Black woman, all I could focus on was the history these trees represented, the symbolic element each part of the tree held, and the stories they continue to tell.

As we drove along Honey Horn Drive, I listened to our tour guide and Gullah Geechee culture expert, the incomparable Emory Shaw Campbell, speak of the trees with an esteem and reverence that gave them a transcendent quality.

His melodic blend of English and Gullah Geechee words took us on a journey, bestowing the history of Gullah culture on his attentive audience in a rhythmic tone that channeled the celestial voices of our ancestors.

“Why are there so many trees?” a tourist innocently inquired.

“The city and state ordinance on trees is extremely strict. You can’t even cut a foot off a tree without permission due to mandates.”

I wondered if these rules were based as much on geological regulations as they were on historical preservations.

I read that these trees hold Spanish moss, which is native to the lowlands of South Carolina. Further research told me that what I observed to be hanging from these trees was neither Spanish nor moss.

Typing the very word “hanging” conjured up images in my mind’s eye I prayed would be erased.

Typing the word “erased” conjured up images of the atrocities committed upon a people by those who strived to erase Gullah Geechee history, their language, and their very existence.

Typing the word “existence” reminded me of the Gullah Geechee culture I ashamedly knew nothing about. And why would I? In the words of Mr. Campbell: “We did not learn about Gullah Culture because, in their minds, it was not American, so why would they teach it?”

But there was nothing more “American” to me at this moment than the sight of those trees.

I saw the “moss” hanging from these trees as the extension of nature that told the tales of pain-filled tears from both Native Indigenous inhabitants and African slaves, both of whom had their lands stolen by outsiders.

The theft of history, the theft of a language, the theft of a way of life.

I saw an incessant sadness in the way the moss was seemingly clinging to the trees, while simultaneously seeming to reach for the land that formerly belonged to its rightful owners.

A stolen people, a stolen land, a stolen identity.

And then there were the roots. The roots were strong, unyielding, and almost spiritual in nature. They were no doubt centuries old. Some were internal, while others were external, physically and symbolically entrenched in the past, narrating a history that many may attempt to erase.

And then there were the tree’s trunks. The way the bark made rough and jagged patterns reminded me so much of scars.

I read a quote that said, “Scars are a testament to your resilience and the healing power of time.” As a person who has many physical scars, I am not sure how much “healing” has taken place.

All I could think of was how the peeling bark reminded me of the peeling on the backs of my ancestors, who were scarred from the repeated whippings of the slave masters. The permanence of these scars epitomized the brutality inflicted by American chattel slavery.

I was reminded of the single tear that ran down Denzel Washington’s cheek when he refused to make a sound as he was whipped in the movie Glory.

The thought of the tears I cried at the sight of his single tear caused my eyes to well up yet again. I fought back against rage at the thought of my ancestors being forced to keep their own rage buried deep inside.

Scars.

I read somewhere that the reason why many African Americans were more prone to keloid-type scarification is because our bodies developed hypertrophic scar tissue as an aggressive healing response to repeated injuries.

I looked at my own keloids: some visible, more hidden, some painful, others numb. I wondered if the physical, mental, and spiritual scars of my ancestors felt the same: still painful or had they become numb.

These trees tell a story: of a painful past of stolen lands and horrendous crimes on humanity, of a continued pain that comes with the constant fight to keep what lands remain in the names of Gullah Geechee families, and an even more painful reality when one looks at the future of a seemingly inevitable gentrification of outsiders who have no reverence for the sacredness of this land.

Do they have any thoughts about the tears the tree moth exemplifies, the history that lies in these roots, or the scars these trunks hold? Do they think about the contributions outsiders are playing on the pain that gentrification is having on people that are struggling to hold onto their lands, their language, their history, their culture, and their way of life? Do they know the story these trees tell, or do they just chop them down, physically and metaphorically uprooting the last preservations of Gullah Geechee culture?

Selah.